In the previous post titled “Privatization and Competition – Part I: Why?” I have stated that the goal of privatization is not merely “disposing of public enterprises to the private sector” because it is difficult to operate state-owned companies (SOEs) like private enterprises and often not feasible. Instead, the aim is to transfer these entities to the private sector, freeing them from inertia and ensuring their efficient operation. In this article, we seek answers to two crucial questions:

1) Is the Competition Authority’s intervention in the privatization process necessary?

2) If the Competition Authority’s involvement is necessary, how should it be done?

Let’s first attempt to answer the first question: First and foremost, it’s impossible to definitively say that the goal mentioned in the first paragraph of this article has been clearly articulated in the privatization practices carried out so far. Especially with the emergence of various motives, including financing budget deficits, “obtaining the highest possible revenue from privatization” often takes precedence over other objectives, negatively affecting the social welfare obtained from this process.

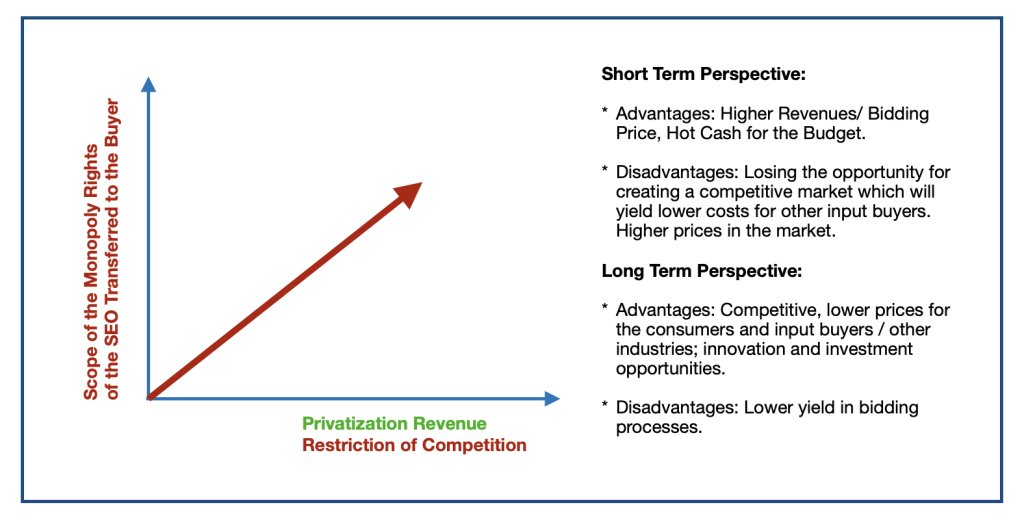

I’m aware that many of you reading this might be wondering, “What other reasonable, natural, and important goal could there be besides obtaining the highest possible revenue from privatization?” In addition to considerations like the strategic importance of some privatized assets, this argument ignores the potential downsides of revenue-focused privatization in the long term. This relationship is also an uncharted territory that academics can explore:

What is being conveyed through the figure above is that, in a scenario where the scope of the monopoly right expands during the transfer of state enterprises or granting of concessions, investors will be willing to pay a higher price for the asset or right. In other words, there is a direct proportion between the degree of monopoly established after privatization and the price paid for the privatized asset. (This relationship can also emerge as a pristine field of study that academics can evaluate.). The scenario illustrated by the figure above can be concretized as follows:

The state is privatizing an economic enterprise with a monopoly right and is evaluating three different options:

a) The SOE will be privatized along with monopoly rights, with no further interference in its operations. The buyer will implement policies and pricing as they see fit.

b) The SOEe, along with monopoly rights, will be privatized. Still, a regulatory authority specific to this sector will be established, which will have the right to intervene in certain parameters, including applied prices.

c) The SOE will be privatized without monopoly rights, a regulatory authority will be established, and licenses will be granted to newcomers to stimulate competition in the market.

Imagine you are an investor with a substantial amount of funds and are looking for a good investment. Which of these three options would be more valuable to you, or in other words, for which option would you be willing to pay the most? I leave the answer to you.

Now, let’s switch to the other side of the table and ask this question: If you are a customer/consumer of the products/services of the enterprise to be privatized, which option do you think should be preferred during privatization? Why?

Let’s move on to the third perspective… As a state authority, you need to make a choice. Which choice would you make in this situation? Why? Answering this question is the most challenging because it depends on “where the government stands.” Focusing on revenue from the perspective of the treasury and finance may become more attractive, and maximizing the revenue from privatization and not doing so might be perceived as a significant risk. In this regard, it would not be wrong to say that the arrow of politics and bureaucracy will likely lean towards option (a).

So, who will advocate for option (c) to be chosen, and who will take the initiative in this regard? It might be unfair to expect this from consumers or civil society organizations in the face of the realities of our country.

In light of the explanations provided above, it is reasonable to review privatization practices with at least a competitive perspective, to share the results of this review transparently, and for the authorities involved in the process to make decisions knowingly, aware of potential risks when it comes to this review function, and in terms of this review function, it seems clear that the Competition Authority is the most suitable place.

In this case, the answer to the question “How should the Competition Authority intervene in the process?” needs to be sought.

As per the current practice, the Competition Board has taken on the role of providing opinions regarding privatization to prevent the transition from a public monopoly to a private monopoly and to evaluate state policies in areas such as treasury and finance in conjunction with competition policies, as well as evaluating the transfer of the privatization subject within the framework of Article 7 of the Law. Therefore, the Authority provides opinions both before and after privatization.

In general, privatization operations involving a private enterprise’s takeover of a public enterprise fall within the scope of Article 7 of Law No. 4054 regarding competitive effects. Transactions that will create or strengthen a dominant position must be prohibited under the provisions of this Article. Whether the provision should be excluded from privatization operations, irrespective of the legal situation, can also be discussed.

With the Competition Board’s absence, as mentioned earlier, the tendency of the administration to choose the “option that will yield the highest revenue” to avoid any suspicion and make a significant income quickly, and passing the problem of dealing with the dominant position that will arise after the transaction like a “ticking time bomb” to the Competition Authority or the regulatory authority – if we “remove” Article 7 from the equation assuming that “Law No. 6 already prohibits the abuse of a dominant position, so there is no need to evaluate privatizations under Article 7.” If this approach were accepted, similar logic could be applied to transactions outside of privatization, and Article 7 of the Law becomes “redundant.” However, developments in US and EU competition law move in the opposite direction: it is generally accepted that, in the evaluation of mergers and acquisitions, in addition to the assessment of “unilateral effects” that focus on the creation of a dominant position per Article 6 of Law No. 4054, the evaluation of the “coordination effects” that will occur as a result of the emerging oligopolies must also be considered.

Therefore, by relying on Article 6 of the Law, the task of monitoring the competitive market and disciplining companies will be taken over by the Competition Authorities or regulatory authorities due to “neglecting” Article 7 – rather than the market dynamics. In the subsequent stages, since the administration will frequently intervene in the operations of the company in a dominant position, the company will, in the long term, be required to obtain approval from the administration for almost every transaction, resulting in an administrative supervision system rather than a market economy. This, in turn, will pave the way for other types of public errors, and privatization’s intended benefits will not be realized. Therefore, following privatization, it is important to show the will to create the most competitive market possible and adhere to it.

After realizing the importance and necessity of applying Article 7 of the Law, it can be asked whether there is a need to distinguish between takeovers in the context of privatization and other takeovers from a procedural perspective.

Given that privatizations differ from the transfer transactions realized by two undertakings through the expression of their will and reached through lengthy negotiations, as they generally adopt the auction method during the privatization process, and especially from the game theory perspective, auctions have different dynamics. Considering that in the privatization context, the administration usually doesn’t have the option to choose its counterparty and negotiate with it, not taking these differences into account procedurally may likely cause serious disruptions. Moreover, changing the conditions after the auction compared to the pre-auction period puts buyers and sellers in a difficult situation, triggers various legal processes, and results in time and monetary loss for the parties involved. Not setting the conditions forth before the auction but revealing them after the auction undermines the credibility of institutions and raises suspicion that the administration is trying to transfer the assets to third parties rather than the winning bidder. Therefore, it has become necessary to develop a different procedural framework specifically for privatizations, and evaluating the transfer transaction within the framework of Article 7 of the Law after the auction is not sufficient on its own.

In line with this need, Communiqué No: 1998/4 was introduced in alignment with the Privatization Administration to evaluate the auction process concerning enterprises that will acquire or strengthen their dominant position by taking over assets subject to privatization and to avoid “surprises” after the auction. Although expressing opinions before the auction is perceived within the framework of legal reasoning as an “expression of intent,” as mentioned above, it is important both for the consistency and reliability of the administration and for the potential abuse of the auction process, as will be discussed below:

The misuse of the auction process can be concretized as follows: After the auction, it is possible for an enterprise to participate in the auction, even if it knows that, according to Article 7 of the Law, the assets will not be transferred to it because it will acquire a dominant position. Thus, the party participating in the action can increase the auction price to force its rivals to take the assets at higher costs! At first glance, this situation may be welcomed since it will increase the privatization revenue; however, it may lead to dire consequences in the market in the long run. That is also why the Competition Board delivered its objections to some firms that are already in a dominant position (or will be in a dominant position after the acquisition of the assets in privatization) when they applied for the bidding processes of the sale of Sabah/ATV assets by the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF).

At the current juncture, it is possible to say that the opinions of the Competition Authority or the decisions made by the Competition Board are crucial for shaping markets in a competitive manner during the privatization process of various state-owned mining companies, a fertilizer company, a telecommunications company, and many other enterprises. In summary, evaluating the relationship between privatization and competition from a multidimensional perspective involving investors, customers/consumers, and government institutions is beneficial. While creating a competitive market is a desired and expected outcome after privatization, it often takes a back seat due to the administration’s focus on privatization revenue. On the other hand, it can be argued that a competitive market is not an absolute necessity, and privatization may aim for different goals, which is also a reasonable proposition. However, if the ultimate goal is the sale of assets owned by the public, the aim is to maximize public benefit and social welfare. One way to achieve this is by creating a competitive market; on the other hand, methods that can increase social welfare by limiting competition should also be considered in the range of preferences.

However, in the current situation, discussions are primarily centered around revenue and competition. Since alternative solutions that are claimed to restrict competition but increase social welfare during the privatization process have not been put forward so far, the Competition Board, having the power to have the final say in the application of Article 7 of the Law and therefore having a decisive role, takes a significant risk in the decision-making process. Some Competition Board decisions that have gained public attention are believed to tie the hands of other administrations, reduce the value of the assets sold, and complicate privatization.

Naturally, in evaluating competitive effects throughout this process, the Competition Authority also carries the risk of making mistakes, which can be used to support the need for a different system. However, the assessments mentioned above, the practices carried out so far, and the potential harms suggest that, in the stage of expressing opinions and making decisions, the risk of making a mistake should be preferred over the risk of not intervening in the process.

Therefore, ideally, a system is needed to maximize privatization revenue, ensure competition, and transparently present, analyze, and discuss any other intended purposes. Until such a system is established, there is an apparent need for an institution that can at least vocally address the impact of privatizations on competition in a manner equal to other actors in the administration and make them aware of the responsibility taken.

* You can read the previous post using the following link: “Privatization and Competition – 1: Why?”

** The original version of this article was published in the “Competition Writings” section of the Competition Authority’s website on March 22, 2012. The opinions presented in the work are those of the author and do not bind the Competition Authority.