Regulations are a concept that actually exists in our lives as long as the state exists, partly due to the development of market economies and partly due to the winds of European Union membership, resulting in more frequent encounters and discussions. Regulation, in its simplest definition, signifies “rules based on state authority.” Therefore, regulations stand apart from other social norms due to their enactment and enforcement by the state. Unlike agreements between individuals, they are not based on free will and voluntariness. They usually do not follow an evolutionary process distinct from other social norms, affect all individuals instead of a limited number, and are subject to the monitoring and enforcement of public authority. As a result, any mistake made in this field will directly affect some actors in society and indirectly affect others. This is where inevitable questions arise, such as “How is good regulation done? What should be avoided when making regulations?”

In this context, considering my own experiences and the experiences of some close friends, I have decided to delve into the practice of regulatory making in Turkey, and with the aim of highlighting the points that should be considered by stakeholders, I have decided to write a series of posts under the title “Pitffalls of Regulation.” Through the articles and anecdotes that will be included in this series, I believe that if progress can be made in at least a few areas, all stakeholders will benefit. As usual, I would like to emphasize that all opinions presented in this series are personal and cannot be attributed to any specific individual, institution, organization, real person, or legal entity.

Now, let’s move on to what “rules based on state authority” are: These rules encompass a wide range, including the constitution, laws, regulations, directives, announcements, and administrative decisions. From this perspective, regulation is essentially another name for legislation, but in everyday life, it is commonly used in a narrower sense, focusing on rules related to markets or economic activities. For this reason, some studies categorize regulations into “social regulations” and “economic regulations.” However, as will be discussed later, since any regulation ultimately has both social and economic effects, this distinction can only be accepted to a certain extent.

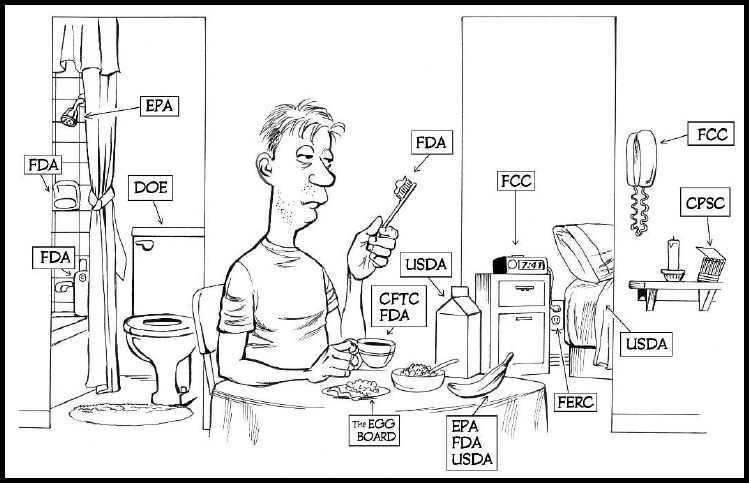

When it comes to how regulations affect us, we are not usually aware of that in our daily lives, every moment of our twenty-four hours is somehow surrounded by the regulations. Susan Dudley discusses the hidden costs of regulations and how they limit our choices in her article titled “A Regulated Day in Life.”[1] Taking inspiration from this article, let’s review one of our days together:

Kaynak: Susan E. Dudley, 2004

As soon as we wake up in the morning and turn on the light, we consume electricity, subject not only to regulations specific to the electricity markets but also to tax regulations. When we attempt to brush our teeth, we seldom think about the inputs of toothpaste, packaging, and the various regulations that apply to the production, sale, and distribution of these products. Similarly, the fees we pay for tap water, wastewater, and road usage (I saw this on my ASKI bill while preparing this text; I’d appreciate it if someone could explain!) and taxes are all demanded from us within the framework of regulations. Opening the refrigerator to have breakfast, we encounter a myriad of regulations: the contents of the food, information on the packaging, the obligation for some packaging to be made from non-recyclable materials, other production standards; the warranty period of the refrigerator, the form of the warranty certificate, the manufacturer’s service obligations, the production of parts and related standards, certification of energy consumption, various taxes related to sales, additional import taxes if applicable – all fall under the realm of regulations. Without dwelling on all of this, let’s say you’ve had your breakfast, gotten dressed, and managed to get into your car to leave for work. Now, let’s talk about dozens of standards related to the car and its components – crash tests, bumper height, minimum sheet metal thickness, permissible emission values, exhaust (environmental), and mandatory traffic inspections – the factors assessed in these, the sanctions for non-compliance with these requirements – sales tax, import (customs) duty, special consumption tax, value-added tax, stamp duties, taxes related to registration, motor vehicle tax, tire tread, and depth. Then, as you turn the ignition, you’re met with fuel tax, value-added tax, profit margins, minimum and maximum price limits, the marking system, the licensing requirements for the stations that provide these services, regulations for rights of usage – all at the forefront of your mind are the many other regulations… If we were to count the entire day, writing or reading the article would take more than a day. Therefore, you can proceed with your work until I complete my writing.

In summary, regulations, whether social, technical, or economic, have surrounded us, and their numbers are increasing day by day. Therefore, the appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency, and feasibility of regulations carry significant importance; hence, legislative, executive, and judicial authorities have significant responsibilities.

Let’s continue our journey in pursuit of effective regulation by further elaborating on the definition of regulation: “Regulations are rules established based on public authority to address a specific problem, creating rights and obligations for actors in society.”

The above definition is inherently normative: it not only defines what regulation is but also how it should be. In other words, while a “rule based on public authority” may qualify as a regulation, it is stated that “this alone is not sufficient for a good regulation.” From this definition, it is possible to conclude that a regulation that does not adhere to the following points would not be considered a good regulation:

- With each regulation, rights and obligations are redistributed by the hand of the state, altering the balance of welfare among actors. For instance, a new standard or requirement introduced from a health perspective for food production will necessitate businesses to incur additional costs, leading to an increase in product prices. As a result, some consumers, while paying a certain price increase, may have access to healthier products, while others might be deprived of consuming that product due to the rising prices or consume it less. Additionally, the exit of certain companies from the market due to an inability to meet the said standard, leading to their employees becoming unemployed, is another example of the (undesired) impact of regulation. As seen in this scenario, choices made by the state result in additional benefits for some actors and negative consequences for others. In such a case, if the necessity of the mentioned standard, its cost, and who will bear that cost are not clearly foreseen, then for the sake of a smaller number of people consuming healthier food, many might be deprived of it. (The requirement of whether HACCP standards for food production or tracking systems for product safety should be mandatory or optional can be discussed in this context). In summary, regulation is costly for the government, stakeholders, and society, and who will bear this cost and why should be clearly defined beforehand.

- Especially for the reasons mentioned above, regulation needs to be based on explicit authority. While having the authority to regulate is a minimum necessity, it is not sufficient on its own: Authority alone does not guarantee the desired impact; it does not legitimize the means and the ends. However, considering that many institutions regulate the same area from different perspectives (e.g., a production facility’s license being overseen by the municipality, taxes by the finance ministry, and various health, environment, customs, trade, and labor social security ministries in different aspects), it is important that regulations do not contradict each other, are consistent, and are conducted in a coordinated manner independent of institutional power struggles.

- Every regulation actually implies a limitation of citizens’ rights to choose. For example, restrictions like not using certain dyes or types of plastic in materials for children not only limit producers’ choices but also consumers’, although with the aim of protecting children’s health and development, considering that without these restrictions, consumers wouldn’t know about them, they would prefer cheaper products that don’t bear this cost, and this could negatively affect children’s health and development. Therefore, limiting the production and/or market entry of these products from the outset is a logical solution. Setting maximum installments for the purchase of electronic devices to curb their imports under the guise of protecting consumers is also an example of limiting the right to choose. (After this regulation, considering that consumers continue to buy these products with bank loans lasting up to 36 months and only an additional ‘financing cost’ is added, the rationality, functionality, and feasibility of this should be carefully analyzed.)

In conclusion, it should not be forgotten that regulation is a “means,” not an “end.”: Especially in regulations targeting the market, it should be constantly kept in mind that markets could function more effectively without intervention, and interventions could result in worse outcomes compared to the pre-intervention situation for businesses, consumers, and the state. In other words, while having the authority to regulate is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient on its own. There should also be a reason that justifies the use of regulatory authority, a problem that needs to be solved. The more accurately this problem, which will constitute the rationale and purpose of the regulation, is defined, the more effective the regulation will be.

However, when looking at the implementation, it can be observed that institutions often respond to the question “Why are you making this regulation?” with “Because we have the duty and authority to regulate this market.” While it is natural for any institution to make a regulation that aligns with its purpose and the requirements of that purpose, it is often overlooked that regulation itself and the act of regulating are not standalone purposes but rather means to an end.

So, what can be done to address all the mentioned drawbacks? This question has been raised in many different countries, and in order to achieve appropriate and effective regulations, a framework known as “Regulatory Impact Analysis” (RIA) has been introduced. This framework has also been implemented in our country through Prime Ministry Circular No. 2007/6 and is mandatory in certain legislative drafts.

The story of regulatory impact analysis will be the subject of my next post. In the subsequent posts, the detection and resolution of other regulatory pitfalls will be discussed.

NOTES:

(1) Susan E. Dudley, “A Regulated Day in the Life”, REGULATION, Summer 2004. @ http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2004/7/mercreportcomm.pdf

(2) Note: As of June 27, 2015, the Prime Ministry Circulars from the year 2007 cannot be accessed on the page where they were previously available. This situation has persisted since at least the beginning of April 2015. Similarly, on www.mevzuat.gov.tr, since it provides a link to this page for Prime Ministry Circulars, there is no way to access the circular from there as well.

(*) All opinions and suggestions presented in this article are entirely personal and not binding from the perspective of any individual, institution, or organization.