The success story of the liberalization of domestic air passenger transportation in our country in 2002 is essential for concretely illustrating the benefits of competition and the relationships between policy design, bureaucracy, regulations, and markets. Some key lessons from this success story are outlined below:

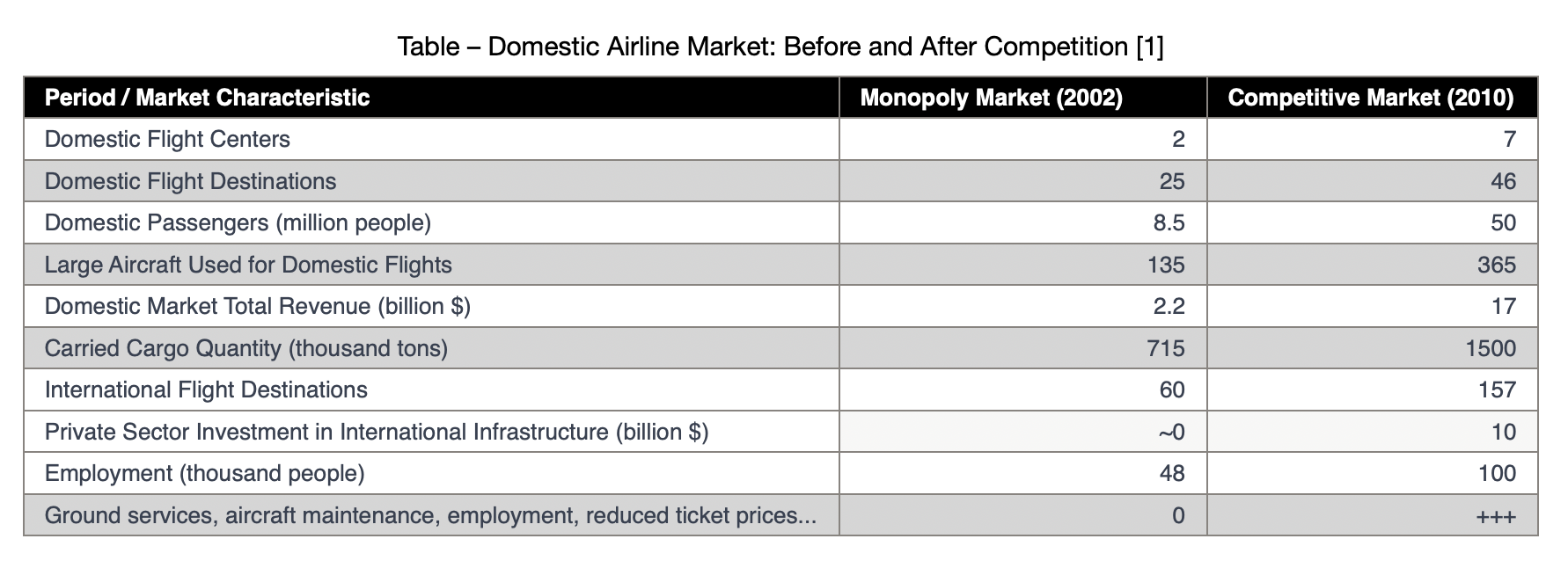

The data relating to the market at the beginning of the liberalization process and afterward are as follows: Turkish Airlines (THY) had a monopoly and operated flights to 25 domestic and 60 international destinations from 2 hubs. With 135 Turkish-flagged large aircraft, THY transported 8.5 million passengers and 715,000 tons of cargo, creating a market worth $2.2 billion. However, by 2010 (within eight years), several significant developments had taken place: The number of flight centers had increased to 7 while the number of domestically accessible airports had almost doubled, reaching 46. Likewise, the number of passengers carried in a year had increased by 580%, reaching 50 million. The number of large aircraft had almost tripled, reaching 365, while the sector’s revenue had surged by 770%, reaching $17 billion. During the same period, cargo transportation had doubled, and infrastructure investments to increase airport capacities had reached $10 billion. In 2002, the sector had employed 48,000 people, which had increased to 100,000 by the end of 2009. Additionally, due to liberalization and partly due to tax reductions on aviation fuel, airplane ticket prices had dropped to nearly the same level as bus ticket prices.

We can summarize the lessons learned from this overview of the market and, in general, the opening of the market to competition as follows:

1 – The opening of a previously closed market to competition has allowed more people to reach many more destinations at a much lower cost compared to the past. This success story stands out in several ways:

2 – Concerns about Turkish Airlines (THY) incurring losses and putting its international operations in danger following the opening of the domestic market to competition proved unfounded. THY, which previously sold expensive tickets in limited quantities, had to lower ticket prices to adapt to competition. As a result, even though profit margins decreased, THY sold many more tickets due to increased demand. In the end, “Turkish civil aviation began its golden age.”

3 – The most crucial point is that the passenger air transportation market is not a “natural monopoly” like energy or telecommunications markets. Unlike Turkish Telecom, which had a legal monopoly right in voice transmission until 2002, Turkish Airlines did not enjoy a legal monopoly right until 2002. The primary reason THY effectively retained its monopoly and why other players had no entry into this market was due to a specific policy decision, the General Directorate of Civil Aviation Decision dated 12.01.1996.

According to this decision, companies planning to transport passengers to specific airports had to meet the following conditions: (1) They had to transport passengers to at least one airport in the eastern and southeastern regions. (2) They had to operate scheduled flights on routes opened in the summer and winter seasons. (3) Private sector companies were only allowed to operate on routes where THY did not have flights or on days when THY’s flights were insufficient, and they were not allowed to operate on days when THY had flights.

Therefore, this example demonstrates that some laws, bylaws, regulations, or administrative decisions can easily and inadvertently eliminate market competition and lead to monopolies. It also shows that poorly analyzed regulations or political/bureaucratic decisions can hinder market development, making citizens purchase services at higher prices, with lower quantities, and keeping the market’s potential employment levels well below their capacity.

4 – The fourth lesson from this example is that markets are not independent of each other, and an increase or disruption in competition in one market can positively or negatively affect other markets. Indeed, liberalization in air transportation has undoubtedly contributed to reducing costs for companies using these services. For example, a small or medium-sized enterprise (SME) manager or an employee could attend a meeting by air rather than by coach, saving time and increasing productivity.

5 – The fifth lesson is that competition does not promise a trouble-free path or a fair and square solution to all market failures. Thus, increasing competition in one market can also increase competitive pressure on substitute products and services. This process needs to be managed well. For instance, until the air transportation market was opened to competition, the excess demand not met by the monopoly was shifted to road passenger transportation. This allowed many small and large coach companies to operate with partially idle capacities. However, the liberalization of air passenger transportation and the reduction in airplane ticket prices increased the competitive pressure on road passenger transportation. This development led to cheaper bus tickets and improved service quality, but it also led companies that could not benefit from economies of scale to exit the market. The policymakers had overlooked that problem. Companies competing for a slice of the shrinking pie occasionally began transporting passengers with free or below-cost prices, sacrificing quality to reduce costs. In response, the Ministry of Transportation partially restricted competition by introducing price floor and price ceiling regulations! The costs and benefits of such regulations or whether they encouraged enterprises to enter into anti-competitive agreements are subject to another discussion. However, there is no doubt that road passenger transportation needs to be restructured to utilize economies of scale and complement bus and railway transportation, especially considering the prospect of rapid development in the railway sector.

The implications of all these developments from the perspective of the interactions among the market, competition, and the state are as follows:

For a market economy to produce beneficial outcomes for society, it is essential to maintain the dynamics of competition in the market. Therefore, in a country that cannot internalize competition law or culture of competition, the contribution of a market economy to the overall social welfare will be limited. However, competition doesn’t always occur naturally and continuously. Hence, it is crucial to remove elements that restrict competition. In this context, elements restricting competition can be evaluated under three main headings:

a. Restrictions on competition arising from the behavior of market actors.

b. Restrictions on competition arising from the structure of the market.

c. Restrictions on competition arising from regulations.

Restrictions on competition arising from the behavior of market actors fall under the scope of investigation and penalties within the framework of Law No. 4054. They are part of the Competition Authority’s jurisdiction.

However, assuming that the Competition Authority, performing its duties effectively, will find solutions to “all kinds of competition disruptions” in the markets would be a significant misconception.

The other two reasons for market failures (arising from market structure or regulations) are outside the mandate of the Competition Authority normally, even if the authority tries to address these via competition advocacy initiatives. Thus, policy proposals regarding addressing these failures can be evaluated as follows:

Intervening with restrictions on competition arising from the market structure can be debated regarding its appropriateness and effectiveness. However, parallel to technological advancement, it is now observed that markets that were previously regarded as natural monopolies can be segmented, and some of these segments can be opened to competition. Therefore, opening these markets to competition becomes a matter of political will and some regulations following a certain technological advancement. Indeed, in the past twelve years, sectoral regulatory authorities have become part of our bureaucratic structure concerning telecommunications and energy markets and have taken part in privatization and liberalization practices.

However, the concepts of a market economy and competition are relatively new to our country compared to developed countries, and it is not possible to say that policymakers and regulators have internalized these concepts. So, despite the progress made, we still need a great deal of improvement in eliminating restrictions on competition arising from the regulations for the following reasons:

As understood from the practice, (i) sometimes public authorities make regulations that restrict competition because they do not trust the market mechanism, (ii) sometimes they are under the influence of market actors, (iii) sometimes they fail to comprehend the impact of the regulations on competition, and (iv) sometimes they believe that restricting competition, as in the case of Turkish Airlines in lesson number three, would be “in the national interest.” The first two reasons are not acceptable by the nature of the business. As discussed below, a guideline was adopted in 2007 to address the third disruption.

As for the fourth option, it is useful to outline a clear policy area: “Preserving competition” is not an absolute goal but a means to protect and enhance societal welfare, balancing private and public interests. Therefore, in some cases, restricting competition can be considered reasonable from the perspective of societal benefit. However, in this regard, it is essential to make decisions objectively, considering the views of the relevant institutions. The method provided for this purpose is Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA). As of 2007, Turkey has introduced “Regulatory Impact Analysis” (RIA), which requires examining the budgetary, sanitary, social, environmental, and competitive effects of draft regulations. However, there is still much progress to be made in this field due to the reasons mentioned below:

Some public institutions are unaware of RIA, and some of those who are aware view it as a burden. Some do not implement RIA because they do not trust the market economy or apply it superficially to fulfill a formality. As stipulated by Prime Ministry Circular No. 2007/6, the RIA process is mandatory for laws and legislative decrees of certain financial sizes. However, as seen in the example above, even a “general directorate decision” that does not have the status of a law, legislative decree, regulation, or communiqué can turn an entire market into a monopoly. Therefore, without outlining a framework that includes even the lowest-level regulations, the benefit of RIA will be limited.

Similarly, it is observed that a lack of transparency in the legislation preparation processes, insufficient awareness of institutions, and the influence of various professional organizations or civil society organizations lead to restrictions on competition in markets through secondary regulatory instruments such as regulations and communiqués.

In summary, it can be said that by changing or eliminating the General Directorate Decision that effectively blocked market entry due to changes in perspectives, a broad vision, political will, and determination, the predicted passenger traffic for 2015, as of 2006, was reached ten years earlier.[5]

On the other side of the coin, there is a problem we will eventually have to face: As a country, we still do not know how many decisions, regulations, communiqués, or directives similar to this decision restrict which markets in what way. More alarmingly, we lack a depth or even a superficial application of an impact analysis mechanism that will prevent such restrictions from arising or ensure that such restrictions are proposed within a consistent policy framework.

As a result, while the answer question “Competition IS INTRODUCED, so WHAT?” stands as a success story, especially for public institutions and regulators, there seem to be many more lessons to be learned from the answer to the question “HOW WAS THE COMPETITION RESTRICTED IN THE FIRST PLACE?”

* The original of this article was published on the Competition Authority’s website in the section “Competition Writings” on 22.12.2011. The views expressed in the article belong to Barış EKDİ and do not bind any institution or organization.

1 The data is compiled from the Symposium on Micro Reforms and Competition Policy for the Turkish Economy, Competition Authority Publications, 2011, (pp. 131-151) and the Civil Aviation General Directorate website.

2 The expression is taken from the June 2009 issue of Skylife, the Turkish Airlines’ magazine.

3 Ekdi, B., E. Öztürk, H.H.Ünlü, K.Ünlüsoy, S. Çınaroğlu, “Rekabet Kuralları ile Uyumlu Olmayan Mevzuat Listesi (I)”, Rekabet Dergisi, Sayı:9, Yıl:2002.

4 03.04.2007 tarih ve 2007/6 sayılı Başbakanlık Genelgesi 5 NTVMSNBC Ekonomi Haberleri, 22.11.2006